History of the Battle at Goldsborough Bridge

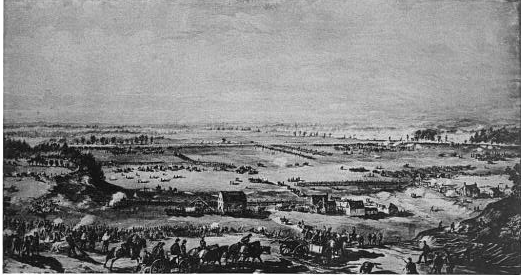

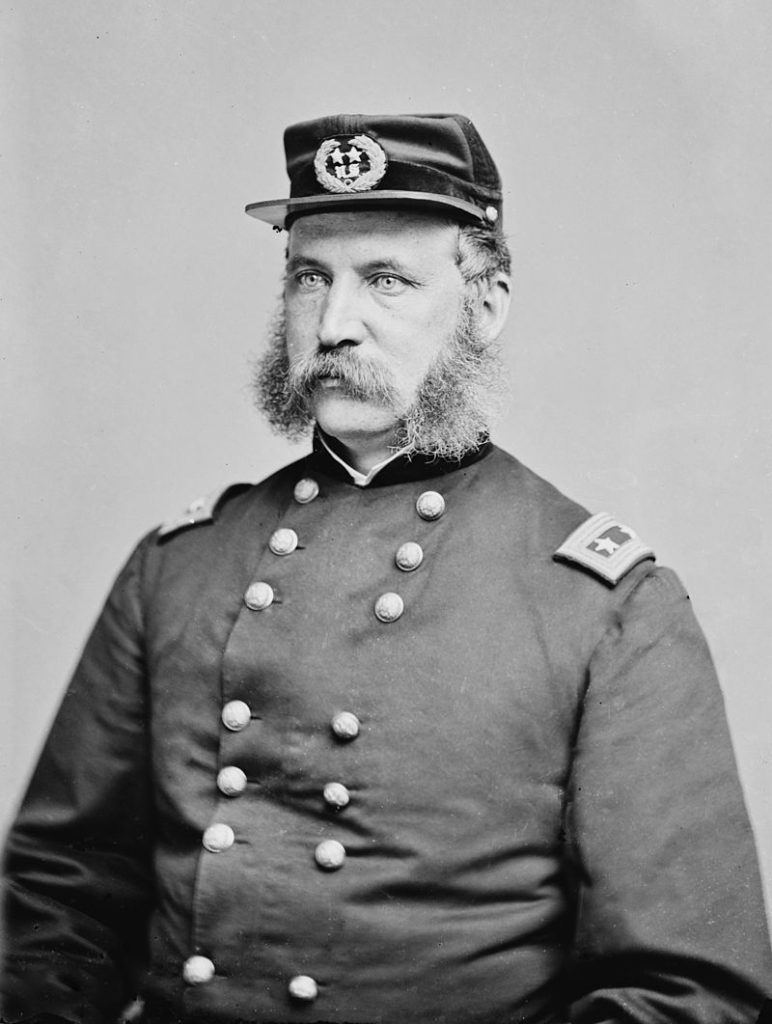

The Battle of Goldsborough Bridge was fought December 17, 1862 at the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad Bridge across the Neuse River, three miles south of Goldsborough, North Carolina. Troops and supplies aboard trains from the Deep South and the port at Wilmington had to cross this bridge on their way to Virginia, making this bridge a vital link in the Confederate supply chain. Because of the intersection of two railroads at Goldsborough, the Wilmington & Weldon and the Atlantic & North Carolina, that city had become one of the most important railroad centers in the South. There were other railroad bridges and depots between Wilmington and Virginia, but the presence of the two railroads at Goldsborough, along with the fact that Goldsborough was only 60 miles from Union-occupied New Berne, made the railroad bridge at Goldsborough an important objective for the Union War Department. The War Department believed that the destruction of this bridge would impact the ability of the Confederacy to wage war, if done in conjunction with a major Union victory in Virginia. A defeated Confederate army, denied re-supply, could be swept aside, leaving the Confederate capital at Richmond vulnerable. The time to implement this plan came late in 1862. In December, the commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, General Ambrose Burnside, was planning an attack on General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Plans were made for the Union commander in North Carolina, General John G. Foster, to simultaneously launch an attack from New Berne against the railroad bridge at Goldsborough. This expedition has come to be known as Foster’s Raid.

by Merrill G Wheelock 43rd Regiment Massachusetts

Foster’s Raid and the Attack at Goldsborough Bridge

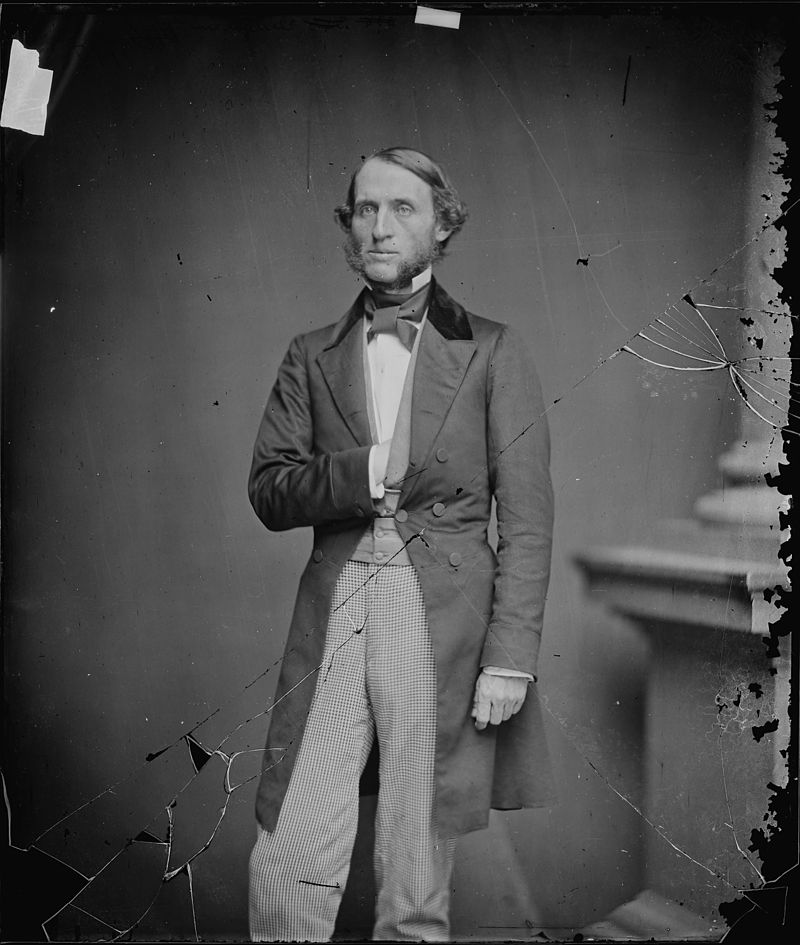

On the morning of Demember 11, 1862 General Foster marched from New Berne with a force of 10,000 infantry, 640 cavalry and 40 guns. After meeting and defeating small Confederate forces at Southwest Creek, Kinston and Whitehall, Foster’s army arrived at the railroad bridge south of Goldsborough on the morning of December 17. Foster deployed his troops and artillery and they began to fight their way to the bridge. The bridge was defended by Confederate General Thomas Clingman, who commanded a small force of less than 2,000 men and a dozen guns. The Confederates fought valiantly but were pushed back west of the railroad and to the north bank of the Neuse River. After a two hour battle a daring assault party of Union volunteers, supported by artillery fire, rushed forward amidst a hail of bullets and set fire to the bridge. Union artillery fire was then brought to bear on the burning bridge, to aid in its destruction and to foil Confederate attempts to douse the flames. In a short while the bridge was destroyed, and then Union troops further damaged the railroad by destroying the tracks for a distance of two to three miles south from the bridge.

Maj. Gen. John G. Folster by Mathew Brady – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection

Hon. Thomas L. Clingman by Mathew Brady – U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

The Confederate Counterattack

Late in the afternoon, Union troops, their objective met, formed up and began the long march back towards their base at New Berne leaving one brigade of infantry and one battery of artillery as a rear guard to cover their withdrawal. On the north bank of the river, Confederate forces had meanwhile been reinforced, and for the first time all day actually outnumbered the Union force that remained on the field. At a council of war, Confederate General Nathan Evans, who had now arrived with a portion of his command, ordered Clingman to cross to the south bank of the river via the county wagon bridge located one half mile upriver from the burned railroad bridge, and attack the Union rear guard. Pursuant to this order, Clingman led four North Carolina regiments, the 8th, 51st, 52nd and 61st, across the bridge, supported by other troops from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Mississippi. Clingman posted the 51st and 52nd North Carolina Regiments near the river bank and hurried one mile to the south with the 8th and 61st. At this point, Evans arrived on the south bank of the river and ordered the 51st and 52nd to attack across the railroad and engage the Union rear guard. These two regiments formed up and crossed a cultivated field west of the railroad then climbed the high railroad embankment. After pausing briefly at the top, they streamed down the eastern face of the embankment shouting the rebel yell, looking to one startled Union soldier like immense gray ants. The sound of the Confederate attack attracted the attention of Union troops that had just left the field, and before the North Carolinians could reach the Union position, additional Union troops and guns had rushed back onto the field. In a short time, the Union force had grown into two infantry brigades and three batteries of artillery, and the odds were suddenly against the Confederate attackers. When within 100 yards of the Union line, the Confederates were met with musketry and double loads of canister fire from up to eighteen Union guns, and the Confederates were turned back with heavy losses. Clingman’s other two regiments, the 8th and 61st North Carolina, were now in position but wisely did not cross the railroad, and instead engaged Union forces from behind the embankment. It was now quite late, and as darkness descended on the battlefield, the firing died down. The Battle of Goldsborough Bridge was over at a cost of nearly 250 men killed, wounded, and missing. Foster’s army once more turned to leave the field but was slowed by having to cross the freezing waters of a swollen stream which flowed behind the Union positions. During their counterattack, Confederate soldiers had destroyed the dam on a millpond through which the stream flowed in an effort to trap the Union rear guard. Now Union soldiers were compelled to cross the stream, which was up to their necks and rushing rapidly. After crossing the stream, the soaked soldiers set fire to the woods on both sides of their line of march, to warm themselves and light their way in the darkness. The Union army arrived back at New Bern just before Christmas 1862. They left in their wake a torn and broken landscape and 1,300 combined Union and Confederate casualties.

The Results of Foster’s Raid

Foster’s Raid was a tactical success for the Union. The vital railroad bridge near Goldsborough was destroyed, temporarily halting the flow of supplies from the Deep South and the port at Wilmington to Virginia. The success Foster enjoyed at Goldsborough was muted however by events in Virginia. Burnside’s attack against Lee at Fredericksburg was a disaster for the Union, which was soundly defeated. The triumphant Confederate army in Virginia was thus able to withstand a temporary loss of supplies and reinforcements from the South, nullifying what would have otherwise been a major strategic victory for the Union. Because of the importance of the Goldsborough bridge to the Confederate chain of supply, men and engineers were rushed to the site and the bridge was rebuilt in a matter of weeks. The next time the Union army would get so close to Goldsborough was on March 21, 1865 when three Union armies over 100,000 strong, captured the city and its vital railroad bridge and depots. These Union armies, commanded by Generals William T. Sherman, Alfred Terry and John Schofield, used the railroad lines at Goldsborough to re-supply for a final push on the state capital at Raleigh, which was to be followed by a link up with General U.S. Grant’s army in Virginia. The three armies left Goldsborough on April 10, 1865; just one day after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia. The war was all but over.